Paddlin’ in the Pines

- Batsto Lake - Batsto ( 39.64682, -74.65327 )

- Batsto River - Wharton State Forest ( 39.71014, -74.66747 )

- Cedar Creek - Berkeley ( 39.90248, -74.24513 )

- Cedar Creek - Lanoka Harbor ( 39.86936, -74.17065 )

- Great Egg Harbor River - Penny Pot ( 39.57547, -74.82239 )

- Great Egg Harbor River - Weymouth ( 39.51339, -74.77889 )

This map shows the trips described in this article.

Hover over marker for name.

by Andrée Jannette

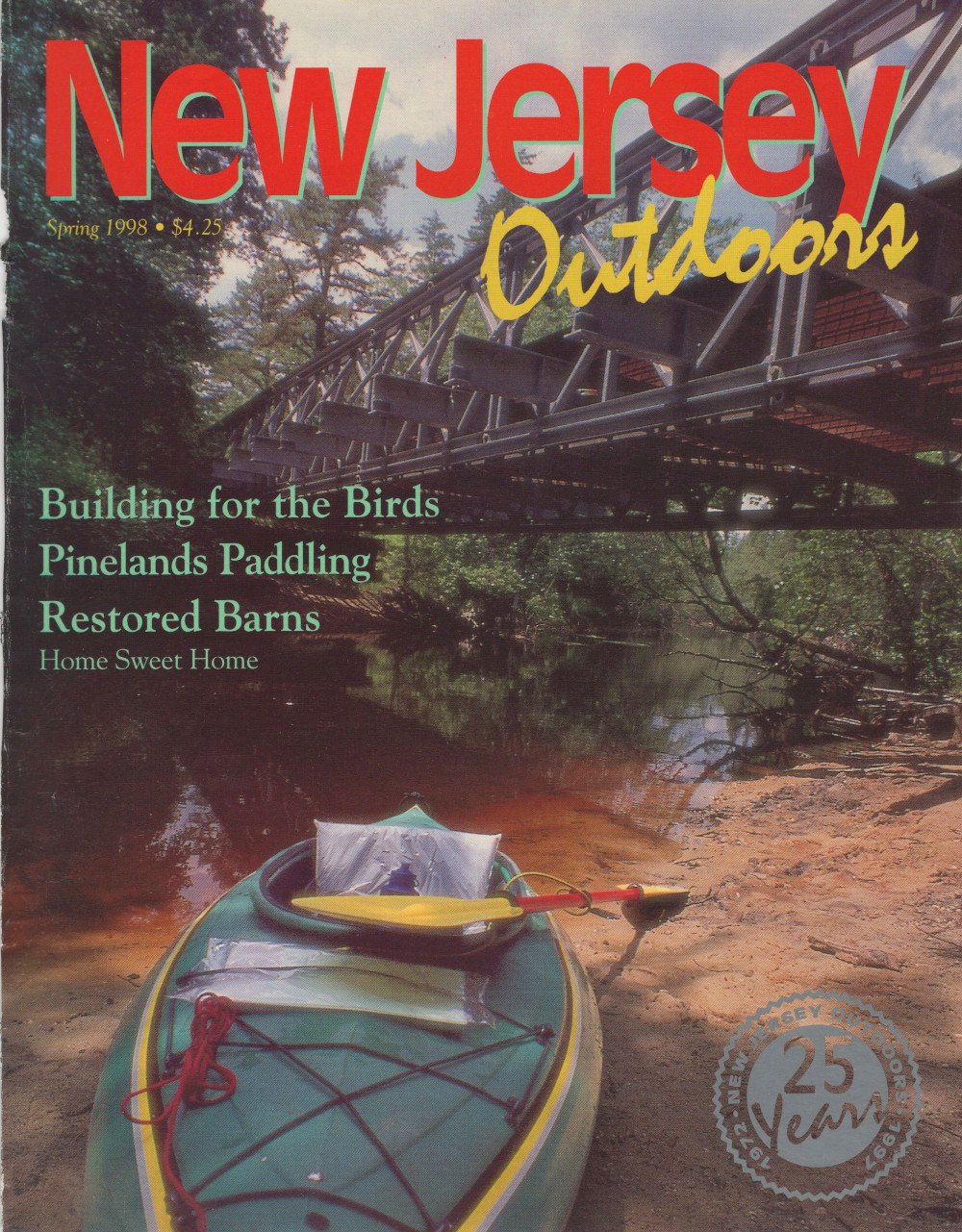

New Jersey Outdoors

Spring 1998

$4.25

If you don’t know how to turn your canoe on a dime when you put in at your first Pinelands river, you will by the time you finish. These are narrow, winding rivers, full of sweeping curves and sharply angled switchbacks. Yet these twists and turns are very much a part of the mystique and the delight of paddling in New Jersey’s Pinelands.

Rounding a bend in one of the region’s rivers is like opening a gift; you never know what you’ll find, whether it’s a young fawn standing stock still by river’s edge or a dazzling display of wild orchids in bloom. Or yet another glimpse of nature at its most serene – sunshine glinting off the tea-colored water of the river; stately Atlantic white cedars rustling softly in the breeze, their vivid greenness sharply defined against a bright blue sky; a dazzling white, sandy river bank offering the perfect spot for a picnic.

All this and more lies within an easy drive of one of the most populated areas in the world. New Jersey’s Pinelands are a priceless recreational treasure for paddlers from throughout the New Jersey/Eastern Pennsylvania/New York region.

“That’s a big part of canoeing here – to get away from it all, to still be in New Jersey, to not have to travel for hours and hours,” explains Gil Mika, Wharton State Forest naturalist. “The convenience of the Pine Barrens is what got me started,” comments Carl Billerts, a long-time paddler and member of the South Jersey Canoe Club. “The sinuousity of the rivers and their constantly unveiling nature got me. They’re always different around each bend. It’s like a motion picture – better than a motion picture!”

“We’re partial to the Pine Barrens,” says Toms River’s Ginny Carty, who with her husband, George, has just completed a personal goal of canoeing in all fifty states. “The flora and fauna are just indescribable. We’re very lucky to have such beautiful rivers so close to home. We use the Pine Barrens year after year, all year round.”

Yet many people remain unaware of this remarkable area, familiar with it only from the signs they see by the side of the road as they speed to and from the Jersey Shore. Those who do turn off onto the smaller roads to explore deeper into the heart of the Pinelands are rewarded with images of striking and unusual beauty, and restored by the serenity of its land and riverscapes.

Anything But Barren

The early settlers called the area the Pine Barrens, believing it to be unfit for traditional agricultural pursuits. Only many years later did they discover the multi-faceted value of the sandy soil that underlies so much of the region and that gave rise to the area’s role as a leader in 18th- and 19th-century America glassmaking and iron works and to today’s flourishing cranberry and blueberry industries.

The Pinelands consists of approximately 1.1 million acres of land that encompass part of seven southeastern New Jersey counties: Atlantic, Burlington, Camden, Cape May, Cumberland, Gloucester and Ocean – almost one-quarter of the state. It is heavily forested, predominantly with oak, cedar and pine trees. “Atlantic white cedar is probably the most characteristic wetland tree of the Pinelands,” says Mika.

There is no industrialization in the region, and little agricultural development other than cranberry and blueberry cultivation. The Pinelands also has a remarkably low population density – only fifteen people per square mile. Those who do make their home in the Pinelands rend to live in or near the area’s few small towns and villages.

In 1978, Congress designated the Pinelands as the nation’s first National Reserve. The next year, New Jersey passed the Pinelands Protection Act. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization declared the region an International Biosphere Reserve in 1983, one of only 247 international sites.

What makes the Pinelands such a unique resource? For one thing, it is the largest “wilderness area” on the Mid-Atlantic coast between Boston and Washington, D.C. Secondly, it is home to more than 1,200 plant and animal species, almost 100 of which are threatened or endangered. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, it sits atop one of the continent’s largest aquifers or underground reservoirs, the Kirkwood-Cohansey, which is estimated to hold 17 trillion gallons of fresh water – enough to cover all of New Jersey in ten feet of water. It is the source of water for the residents of the small towns and villages that sporadically dot the Pinelands, providing them with some of the purest drinking water in the world. All the rivers, streams, bogs and swamps of the Pinelands originate from this aquifer. No water comes into the Pinelands from rivers or streams outside of the area.

One of the first things you’ll notice about the rivers and streams of the Pinelands is the unusual tea color of the water. This is caused by a combination of the high iron content of the soil and the tannin from the Atlantic white cedars that are such a dominant part of the Pinelands landscape. Depending on the season, recent rainfalls and the nature of the individual river, the color can range from slight beige to almost black. Despite its appearance, the water of the Pinelands is pure and unpolluted.

Batsto River

The Batsto River, in Wharton State Forest, is perhaps one of the most beautiful of the Pinelands rivers. Not as easily accessible as some of the other rivers, it is more private, more secluded. Once you are on it, floating peacefully down its narrow main channel with sunlight filtering through the extensive forest of cedar trees that lines its banks, the modern day world with its worries and cares seems a million miles away.

“There are trees along the Batsto that you don’t find along the other streams. A lot of white cedar that look whitish. They have a completely different appearance. It’s like being in the middle of a lost tribe,” says Billerts.

“The Batsto and the Oswego are my two favorite rivers,” says John Krais, chairman of the canoe advisory committee of the Outdoor Club of South Jersey. “There’s the least amount of intrusion. On both rivers you can do an entire trip without a road coming across.” It is rare to hear a man-made noise of any sort once you are on the Batsto. Even if there are other canoeists on the river, the twisting turns of the Batsto soon hide them from view, leaving you to enjoy the peace and solitude of the river.

The most common put-in spot for the Batsto is at Quaker Bridge, off Route 206 in Atsion. From here down to the take-out at Batsto Lake, it is about 7 miles or approximately four hours. When planning your trip, figure on an average speed of one and a half miles per hour for a canoe, slightly faster for a kayak.

For the first third of your trip on the Batsto, the river meanders through cedar and pitch pine forests. Blueberry and huckleberry bushes grow among the trees nearest to the river. Cranberries grow at the water’s edge. Swaying rushes bend with the slow current, just brushing the surface. At this point you are in the center of Wharton State Forest, the largest single tract of land in the New Jersey State Park System. It is almost impossible to believe you are within 30 miles of both Atlantic City and Philadelphia.

About an hour into the trip, bends in the river reveal sunlit banks of soft, white sand, providing wonderfully quiet places to get out, stretch the legs and have lunch. Two-thirds of the way down the Batsto, the river opens out, growing wider, with more open space. Off to both sides of the main channel there are now pools and marshes where wild orchids, irises, pitcher plants and lilies can be found in season – late April to May is the best time to catch them in bloom.

“In spring, there are a lot of orchids blooming,” says Mika. “Along the rivers, check out some of the stagnant, very shallow water areas. May and June are best for variety’s sake in the wetlands area.” If you’re lucky, perhaps you can spot one of the Pinelands’ endangered species, the Pine Barrens tree frog. It’s small and brilliantly colored – bright emerald green with a broad band of lavender bordered by white that runs from its head down along its sides.

As you approach Batsto Lake, a man-made lake that’s part of historic Batsto Village, the river’s main channel becomes hard to identify as it meanders in wide turns through lush growths of grasses and reeds. Follow the moving water that’s clear of growth – that’s the main channel. The river doubles back on itself again and again as it flows through this area, but regardless of how tempting it looks to take a shortcut and push through across patches of grass and reeds, don’t do it. That maneuver often has resulted in people getting stranded and having to walk their canoe out.

The take-out for Batsto is about a half-mile on the right as you’re coming down the lake. It is marked by yellow bands painted around two tall pine trees. The lake itself can often be a push, especially at the end of the day. It’s shallow, and a brisk headwind can make for a hard paddle to the take-out.

Great Egg Harbor River

[Paul Hollerbach]

The Great Egg Harbor River is a favorite with veteran Pinelands paddlers. “It’s like visiting an old friend,” jokes Warren Wittman, a long-time member of the South Jersey Canoe Club. “When I die they’re going to rename that river after me.”

One of the most commonly-used put-ins on the river is at Penny Pot Park on Eighth Street in Folsom. A good take-out spot is in Atlantic County Park at Weymouth Furnace, on Route 559. This makes for about an eight-mile, or five-hour, journey.

Once you put in at Penny Pot, you enter a peaceful, tree-lined world of gently flowing water. The banks of the river are lined with the pines, blueberries and huckleberries so characteristic of the Pinelands. The Great Egg winds its way slowly and gently towards Weymouth. It’s an easy river that carries you along, requiring little in the way of paddling. After about an hour, you’ll see a number of sandy banks that are ideal for picnicking, including one long, broad spot that’s located at a sharp bend in the Great Egg. After you pass through this section, houses along the river become more frequent.

At the end of your journey, the Great Egg rounds a tight turn and ahead are two bridges. Through the first, you can see what’s left of the historic Weymouth Furnace and the adjacent parking lot. Within a few yards, as you continue on, there’s a very sharp curve in the river where the current can create a short stretch of white water. At this point, you pass under the second bridge and arrive at the take-out point.

The only down side I found to the Great Egg is that at times you do hear traffic noise from nearby roads, in particular Route 322. But even this man-made intrusion seems to fade away as you relax more and more into the experience of going with the flow of the river.

Cedar Creek

Most of this waterway is within the boundaries of Double Trouble State Park, which consists of more than 5,000 acres of Pinelands habitat. There are a number of canoe accesses to Cedar Creek; I used Ore Pond just off of Route 530 in Berkeley Township. The most frequently used take-out point is at a recreational area off South Street in Lanoka Harbor. An old train trestle spans the creek at this point and a pump station can be seen on the other side. From Ore Pond to this take-out is about a four- to five-hour trip.

Cedar Creek offers paddlers a beautiful journey through the Pinelands environment. The creek’s waters run deep and clear, with only a faint blush of the characteristic tea color, as it winds its way through small islands and outcroppings of cedar on the first leg of the journey. Blueberry and cranberry bushes are everywhere.

The creek is very open to the sky at this point and sunlight dances off the water. Everything seems very bright, clear and clean. Grasses and rushes are abundant, providing paddlers with as much to look at below water as above. “My brother took me for a canoe ride on Cedar Creek in the 1960s,” says George Carty. “I fell in love with it. I couldn’t wait to introduce my wife to canoeing. We’ve been paddling ever since.”

High-voltage power lines overhead mark the transition from narrow creek to large open pond as Cedar Creek flows into an old reservoir. The pond is one of stark beauty, filled with the bare bones of dead trees jutting against the sky. “We call it the Petrified Forest,” says George Carty. “They use it for the cranberry bogs.”

The pond is a shallow one, so it can be a hard paddle on a windy day. At the end of the pond is a dam. You need to portage at this point. Be aware that the dam was constructed of concrete and not of soft sand as it first appears from the distance. The surface is rough and sharp stones jut from it. Watch your boat and your feet during landing and portage.

Downstream from the dam, Cedar Creek narrows and becomes shadier. There’s ample evidence of beaver activity, with dams to the left and right of the main channel and plenty of works in progress along the river banks. It’s amazing to see 10-inch trees still standing, albeit precariously, after they have been gnawed almost all the way through. “We’ve seen beavers and otters on Cedar Creek,” says Ginny Carty. “I’ve come face to face with them. It startles me and it startles them.”

At frequent intervals you can spot small wellings of spring water entering the creek, infusing more clear, cold water into the main channel. A few hours into the journey you’ll pass under a wooden footbridge. This is part of the state park’s nature trail. Just on the other side of the bridge is a lovely small pond, encircled by cedars, where it’s pleasant to drift peacefully for a moment or two before continuing on your way. After this point the creek begins to more closely resemble some of the other rivers and streams in the Pinelands with stands of cedar gracing its banks and shading the water.

During the course of your journey on Cedar Creek, you pass under the Garden State Parkway and Western Boulevard. A sharp turn on the creek brings the pump station and railroad trestle into view. You need to come around through the trestle to take-out. The only down side to the trip on this lovely creck was the unwelcome presence of beer cans and bottles along the way. There werent many, but they did show up at fairly frequent intervals, disturbing the appearance and appeal of this otherwise pristine waterway.

Other Pinelands Rivers

The Batsto and Great Egg Harbor rivers and Cedar Creek are only three of the many waterways that offer unique and memorable experiences for paddlers in the Pinelands. “Each river, while it may share certain characteristics with other Pinelands waterways, has its own personality,” explains Hartley Tucker, a member of the South Jersey Canoe Club, “though I never met a river I didn’t like.”

The other principal rivers in the Pinelands are: several branches of the Rancocas Creek in the northwest section of the Pinelands; Maurice River in the south; the Westecunk and Oyster creeks, and the Toms, Metedeconk and Manasquan rivers in the northeast; and the Mullica River and its tributaries (the Wading and Bass rivers, and the Nescochague and Landing creeks) in Wharton State Forest. The Oswego River and Tulpehocken Creek flow in to the Wading River, which is thought of as the “party river” during the height of the season.

near Batsto is a real crowd-pleaser. [Herb Segars]

Tips on Canoeing the Pinelands

The rivers in New Jersey’s Pinelands often have as many twists and turns as a corkscrew. Know your paddle strokes before you start out or get someone to teach you. Otherwise you’ll be spending most of your time disentangling yourself from riverside bushes and tree branches or – in the worst-case scenario – drying yourself off after an unplanned dunking.

“The streams here, on the whole, are narrow,” explains Mike Mangum, chief naturalist of the Ocean County Park System. “They wind around a lot and there are obstacles in the water. It takes some decent canoeing skills to canoe these rivers and have a good time.”

“It’s not like paddling around a pond,” adds Tucker. There’s a continuous series of S-turns. There are strainers, low branches over the water, and “alligators” – obstacles in the water. You have to be able to read the river. You have to know how to handle your canoe. “If you’re coming around a tight turn and all of a sudden there’s an obstacle and you’re on the wrong side of the river to get around it, you better know what you’re doing.”

According to veteran paddler Krais, the typical novice mistake is to paddle too much into a turn. George Carty suggests staying on the inside of the turn, but he advises paddlers to carry a dry change of clothes.

Blowdowns – downed trees that block a paddler’s path – are common occurrences in the Pinelands. The canoe liveries and local canoe clubs try their best to keep the rivers clear, but if you’re going out of season or on a little used section of a river, you might want to take a saw with you.

Renting A Canoe/Kayak

There are a number of canoe liveries in the area where you can rent a canoe or kayak, and they will transport you to the put-in point. Some of the liveries provide hauling services for people who have their own boats. They also are a great source for information on water and river conditions; call them before you go. For a full list of canoe liveries, contact Ocean County Parks and Recreation, Wells Mills County Park, at 609/971-3085, or the Pinelands Preservation Alliance at 609/894-8000.

Although the Pinelands’ waterways are supplied by the Kirkwood-Cohansey aquifer and therefore are not as susceptible to fluctuations in rainfall as flood-plain rivers are, they do become shallower in mid to late summer. The lack of rainfall last summer and fall brought down some of the river levels so much that they were virtually unnavigable by canoe. In particular, the Mullica and Oswego Rivers frequently become too shallow to canoe by the end of summer. Additionally, the Oswego’s water often is diverted for the cranberry harvest in October and to flood the plants as protection during the winter months. Always call before you go to check on conditions.

Picking the Time

Everyone has their own preference as to the best time to go. The middle of summer and weekends are the worst times if you want a solitary, communing-with-nature experience on one of the rivers in the Pinelands. If you can, go in early morning or on weekdays.

“There’s a window of opportunity in April, when the swamp maples come into bloom,” says Billerts, noting that they’re red like a poinsettia, in striking contrast with the green of their leaves and the marsh grass. “There will be a week when it’s absolutely brilliant. The red and green and the sense of light and openness.”

Mangum also thinks April is a great time to explore the Pinelands rivers. “If you hit it at the right time, the herons are migrating,” he says. “We don’t go in July and August,” explains Wittman, “… too many bugs, too many spider webs.” But he adds, “Anytime I get in a boat I enjoy myself. Anytime.”

Although Joy Krais prefers springtime, with its beautiful flowers, her husband casts his vote for the fall, when he enjoys the reflection of fall foliage on the water. “It’s so clean, there’s so very little of that left. It’s like something that’s still here for us to enjoy,” he muses.

The Cartys love winter paddling. George describes such a day on Cedar Creek: “It was a Sunday, right after 5 to 6 inches of snow fell. It was clear as a bell, with a beautiful blue sky.” Ginny adds, “It was like a winter wonderland.”

What to Watch Out For

Ticks, ticks, ticks. The deer tick is abundant in the Pinelands. The prime season runs from April to November, so be sure to take common-sense precautions: Use bug spray, wear light-colored clothing, roll your pant legs inside your socks, and always check for ticks after any outdoors excursion. People think that they’re not going to be bothered by ticks when they’re out paddling on the water. Wrong. Brushing through overhanging branches, portages and other rest stops can put you in the position of providing livery service to some very unwelcome customers.

“Don’t take going into the wilderness lightly,” Tucker advises. Be prepared. Never overestimate your own abilities, and never underestimate the potential of things to go wrong.” The Pinelands rivers in Wharton State Forest are miles from paved roads. They are truly wilderness areas. There are no quick exits if you get in trouble or get hurt; you’ll have to either paddle or hike out. Wittman makes it a point never to go by himself. “What am I going to do if I upset? If you have someone with you, well you’ve got help of some kind,” he says.

Krais thinks that one of the biggest mistakes people make in the Pinelands is that they think they don’t need to wear a PFD (personal flotation device). “There are some deep spots,” he explains. “You can hit your head or get tangled in the branches of a blowdown. Wear your life jacket.”

Also, keep in mind that hunting is allowed in New Jersey’s state forests, so check with park rangers about what’s going on and where so you’ll feel and be safer when you’re out paddling around.

A Final Word

Paddling in the Pinelands is an incredible experience, relaxing, peaceful and restorative. Take an afternoon or a day and visit this beautiful and unique area. And when you are out and about exploring the wonderful rivers of New Jersey’s Pinelands, Ginny Carty’s best recommendation for total enjoyment is to “just go with the flow!”

Andrée Jannette is a freelance writer who lives in Swarthmore, PA.

Paddling in the Pinelands is an incredible experience – relaxing, peaceful and restorative.

Editor’s Note:

This article from over a quarter-century ago also contained a list of canoe liveries that I did not include, as I doubt many of them still exist; nowadays kayaks are cheap to own. However, the rivers and the access points are still there. There are miles and miles of waterways you could paddle in South Jersey, the difficulty is finding public access. Most of the shorelines are either private property or muck and sawgrass. Most of the access points listed here do have nearby rental operations, you can look them up yourself. I added the Toms River and Mullica River sites.

Questions or Inquiries?

Just want to say Hello? Sign the .